Artists Statement/Bio

A native-born Chicagoan, Jack developed formal composition and the aesthetics of positive and negative space at the Cleveland Institute of Art After returning to Chicago in 1984, he began to illustrate private homes and public buildings on the North Shore. He also began to notice, for the first time, the serious pride and appreciation Illinoisans had for their area’s architecture, particularly that of Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan, and Daniel Burnham. Not having perceived Chicago’s architecture in his youth, books Jack read and lectures and walking tours he participated in around the Loop and along the Chicago River revealed its heritage and historical significance more concretely. Many coffee table books, post cards and other gifts and memorabilia of architectural photography were being sold on Michigan Avenue, as was art composed in water color, pen and ink, and oils in the River North’s SUHU artist’s district.

But something was missing in the fine art of the old buildings he loved to walk past and study. Mr. Nixon realized the contemporary art did not complement their excellent craftsmanship. Contrary to old, intricate, architectural prints he had seen in his college research, the vast majority of modern artistic interpretation was too impressionist to capture their refined elegance. The warmth and human qualities of the beautiful stone and terra cotta embellishment of low and high reliefs were being lost in the art of general street scenes.

And richly detailed, framed architectural prints of European cities were hanging in corporate offices and retail shops all over the town? Prints of old European engravings and etchings were filling a void in the art market that should have been filled with ornamental prints of Chicago. Either no one had taken advantage of the opportunity to supply the public these graphics or no one had realized the market’s decorative needs.

It is human nature to create ornament and beauty in our surroundings as well as adorning decoration placed upon on ourselves. It has recently been discovered by archeologists in Gibralter and Italian caves that “unimaginative or Luddite” pre-modern Neanderthal man used feathers, paint, and seashells for our first known use of human symbolism in personal decoration at least 44,000 years ago.

The world has seen the fusion of architecture and arts and crafts in the caves of Lascaux, the tomb of Tutankhamun, the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, the myriad Baroque cathedrals of Europe, and the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893 [(my apologies to Louis Sullivan.)] After many decades of an austere, international modern movement were “Less is more,” architecture today is returning to a more conscious collaboration between the artist, [the artisan,] and the architect. Art in Architecture: The Collaborative Spirit of the Interwar Period in Detroit, 1919-1941, Tawny Ryan Nelb, Archivist and Historian

In the last two decades, an intensified interest in the preservation of our natural environment has evoked a broader understanding of environmental quality: environment is both natural and man-made. This expanded concept of environment is a recognition that buildings and neighborhoods should be preserved for reasons that go beyond historic or architectural significance. A sense of place and cultural continuity are increasingly accepted as genuine needs in American society. Equally widespread is the growing recognition that “quality of life” is intimately related to hospitable surroundings- in terms of scale, texture, and a design of place. Architecture is the art that defines our sensibilities more than any other form of visual expression. Warm, natural materials and elements of craftsmanship in ornament bring value to our surroundings. As we build structures of glass and steel that have few elements to celebrate our own humanity, we have grown to appreciate older buildings that relate more to us.

Conservation, renovation, or restoration of fine, old buildings made of limestone and terra cotta have helped to save our deteriorating American urban environment. But, with little graphic reinforcement, how could the education, awareness, and appreciation of America’s classic architecture be manifested more concretely to the public on a day to day basis?

Inspired by the eighteenth century Italian illustrators and printmakers like Giovanni Battista Pirenasi (1720-1778) and Guiseppe Vasi (1710-1782), the beautiful architectural engravings of the antiquities portfolio Description de l’Egypte (1809) of Egypt’s ancient ruins shortly after Napoleon’s Armée d’Orient withdrawl from the middle east, the nineteenth century French Beaux-Arts antiquary watercolorists og Greek and Roman ruins, and the French-American ornithologist, John James Audubon (1785-1851), Jack Nixon saw the potential for new, high quality architectural graphics of Chicago’s and America’s historic buildings, monuments, and ornamental decoration that could rival the etchings and engravings of ancient Rome, Athens, and Egypt. In 1987 he began to produce a series of master original pencil drawings called: “CLASSIC CHICAGO: THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE.”

It is rare for a curator to come across an artist with Jack Nixon’s talent. With a superb sense of composition and space, while practicing excellent draughtsmanship and rendering, Jack documents and editions grand urban landscapes and vignettes of Chicago with its buildings, monuments, and decorative stone fragments that glorifies the city’s late 19th and early 20th century neo-Classic, Gothic, and Art Deco architectural styles.

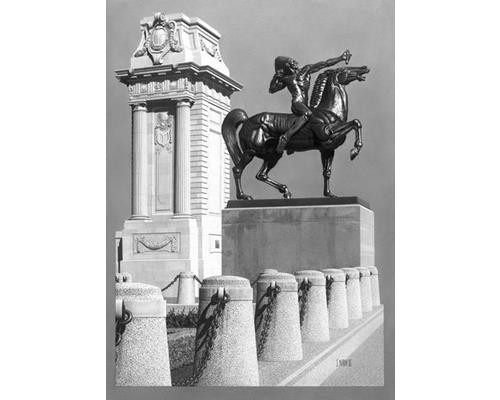

Working graphite on paper, self-supplied with hundreds of photographs for reference, he achieves a special vision of Chicago that goes beyond reality. Mr. Nixon’s drawing of bas relief, such as the four sculptures on the corner houses of the Michigan Avenue Bridge become fine trompe l’oeil reliefs [french for “to fool the eye”]. Deftly exhibiting [Ivan Mestrovich’s] two bronze Indian equestrians in Grant Park in bright light isolated from any background authors a new set of graphically substantial icons that match their monumental presence at Michigan Avenue and Congress Boulevard.

The Wrigley, Tribune, and Medinah Spires drawing casts a pleasing balance of three spectacular buildings in the best possible light and juxtaposition. Mr. Nixon has subtly crafted a strong contrast between man’s hard, linear, vertical ediface with nature’s soft, billowing sky that creates a forceful three-dimensional confrontation with the viewer and these historic structures that bysteps weak cliches associated with minor, less adroit illustration.

A master of Realism, displaying a new standard of old-world representation, Mr. Nixon provides us a uniquely contemporary view of architecture as art. It has been a pleasure for the Union League Club to debut Jack Nixon’s work. And I urge everyone who gets the chance, to view them in person. Slides and prints, although accurate, only suggest the powerful impact of the originals.

Dennis Loy, Curator

Union League of Chicago